Growing up as a white girl in Pennsylvania, I was taught that being tan was beautiful. My wealthier classmates would go on vacations to Florida in the winter, coming back with the most glorious tans. And the moment that it started getting warm, everyone would spend excessive amounts of time outside in an effort to get as dark as possible. I hated this charade for completely banal reasons. There was no way to read a book when lying on my back (without limiting sun exposure) and I hated propping myself up on my elbows. I preferred to read indoors in chairs meant for reading. Needless to say, I didn’t get the point of tanning. Still, there were many summers when I tried. Status was just too important.

When I first went to Tokyo, I was shocked to find Shibuya covered in whitening ads. Talking to locals, I found that “white is beautiful” was a common refrain. As I traveled around Asia, I heard this echoed time and time again. I learned that those with Caucasian blood could get better acting and modeling jobs, that black Americans couldn’t teach English to Hong Kong kids (even though white Europeans who spoke English as a second language could). Whiteness (and blondness) was clearly an asset and I got used to people touching my hair with admiration. I was completely discomforted by this dynamic, uncertain of my own cultural position, and disgusted by the “white is beautiful” trope that was reproduced in so many ways. My American repulsion for the reproduction of racist, colonialist structures was outright horrified.

At some point, I went on a reading binge to understand more about whitening. It was just out of curiosity so I can’t remember what all I read but I remembered being startled by the class-based histories of artificial skin coloring, having expected it to be all about race. Apparently, tanning grew popular with white folks earlier in the 20th century to mark leisure and money. If you could be tan in winter, it showed that you had the resources to go to a warm climate. If you could be tan in summer, it showed that you weren’t stuck in the factories for work. (Needless to say, farmer tans are read in the same light.) Traipsing through the literature, I also learned that whitening had a similar history in Asia; being light meant that you didn’t have to work in the fields. Having always assumed that tanning was about looking healthy and whitening was about reproducing colonial structures, I found myself struggling to make sense of the class-based cultural dynamics implied. And uncertain of how to read them. Hell, I’m still not sure what to make of it all.

Of course, growing up in the States, I’ve seen a different version of light-skin fetishization. One that stems from our history of racism. One that is perpetuated in the black community with light skinned black folks being treated differently than dark skinned black folks by other black folks. So I don’t feel as though I have a good framework for making sense of how race is read in different countries. Or how it’s tied into the narratives of classism and colonialism. Or what it means for modifying skin tone. All that I know is that the marketing of skin coloring products is far more complex than I originally thought. That we can’t see it simply in light of race, but as a complex interplay between race, class, and geography. And that how we read these narratives is going to depend on our own cultural position.

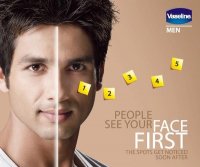

So, moving forward to 2010, Vaseline puts out a Facebook App for virtual skin whitening targeted at Indian men. This virtual product is an ad for its whitening product, but it also serves to allow users to modify their skin tone in their pictures. Needless to say, the signaling issues here are intriguing. I can’t help but think back to Judith Donath’s classic Identity and Deception in the Virtual Community. But there are also huge issues here about race and class and national identity. As people start finding out about this App, a huge uproar exploded. Only, to the best that I can tell, the uproar is entirely American. With Americans telling other Americans that Vaseline is being racist. But how are Indians reading the ads? And why aren’t Americans critical of the tanning products that Vaseline and related companies make? Frankly, I’m struggling to make sense of the complex narratives that are playing out right now.

So, moving forward to 2010, Vaseline puts out a Facebook App for virtual skin whitening targeted at Indian men. This virtual product is an ad for its whitening product, but it also serves to allow users to modify their skin tone in their pictures. Needless to say, the signaling issues here are intriguing. I can’t help but think back to Judith Donath’s classic Identity and Deception in the Virtual Community. But there are also huge issues here about race and class and national identity. As people start finding out about this App, a huge uproar exploded. Only, to the best that I can tell, the uproar is entirely American. With Americans telling other Americans that Vaseline is being racist. But how are Indians reading the ads? And why aren’t Americans critical of the tanning products that Vaseline and related companies make? Frankly, I’m struggling to make sense of the complex narratives that are playing out right now.

What intrigues me the most about the anti-Vaseline discourse is that it seems to be Americans telling the global south (which is mostly in the northern hemisphere) that they’re being oppressed by American companies. The narrative is that Vaseline is selling whitening products to perpetuate colonial ideals of beauty. In the story that I’m reading, those seeking to consume whitening products are simply oppressed voiceless people who clearly can’t have any good reason for wanting to purchase these products other than their own self-hatred wrt race. (Again, no discussion of fake tanning products.) And in making Vaseline out as an evil company, there’s no room for an interpretation of Vaseline as a company selling a product to a market that has demanded it; they’re purely there to impose a different value set on a marginalized population. Don’t get me wrong – I think that our skin color narratives are wholly fucked up and deeply rooted in racism. But I’m not comfortable with how this discussion is playing out either. And I can’t help but wonder for how many people the Vaseline App controversy is the first time they’ve seen skin whitening products.

This uproar is interesting to me because it highlights cultural collisions. These products are everywhere in Asia but they’re harder to find in the States. Yet, with social media, we get to see these cultural differences collide in novel ways. When we go to foreign countries and talk to people from different cultural backgrounds, we learn to read different value sets even if they bother us. We have room to do that in those contexts. But when we encounter the value sets online sitting behind our computers in our own turf without a cultural context, all sorts of misreadings can take place. I’m seeing this happen on Twitter all the time. Cultural narratives coming from South Africa that mean one thing when situated there but are completely misinterpreted when read from an American lens. I love Ethan Zuckerman’s amazing work on xenophilia. But I can’t help but be curious about all of the xeno-confusion that’s playing out because of the cultural collisions. And I worry that us Americans are just reading every global narrative on American terms. Like we always do. And while this might be great for challenging colonialism, I worry that it is mostly condescending and paternalistic.

And that leaves us with a difficult challenge: how do we combat racism and classism on a global scale when these issues are locally constructed? How do we move between different cultural frameworks and pay homage to the people while seeking to end colonialist oppression? I don’t have the answers. All I have is confusion and uncertainty. And confidence that projecting American civil rights narratives onto other populations is not going to be the solution.

As always Danah you skip right past the reactive bullshit, dig to the heart of the issue, and then bubble your way back up by then providing context for the reactions.

Powerful work.

-Matt

As someone who grew up in Asia, I felt that the propensity towards skin whitening was rooted mostly in classism and not racism(we are after all, mostly all the same race). Given, they do often overlap, but asian racism is whole topic. A lot of racism towards blacks for instance, is possibly based more on stereotypes in media than in an actual rejection of skin colour(asia loves american media…but there just hasn’t been many positive depictions of black people in them). I’m not excusing it, of course – just saying that asian racism is much more complex than skin colour, but at the same time, can be painfully simplistic…

The outrage re: Vaseline does come across as very condescending. At the same time, I can see how an American company creating a skin whitening product is not exactly the same as an Asian company creating one(Shiseido has an entire line!)

Anyway, I agree!

This marks the first time that I’ve ever heard of skin whitening in product form. No doubt because I’m a white Guy from Ohio who has always been sold the opposite.

I had a similar reaction to a similar situation a few years ago: http://www.beginningwithi.com/oped/culture.htm

It can still be a form of colonial oppression because Vaseline is not merely selling to a market demand, but helping to create it. Through apps like this, certainly… and in sooo many other ways I saw when in China. (Such a pain trying to find skin products that don’t bleach!!!)

This kind of pattern has been thoroughly documented in the past, both from the West reaching out to create ‘problems’ that needed commercial solutions in the ‘Global South’ or on home turf.

My favorite example is perhaps the demonification of female body hair. Once people start wearing short sleeves or skirts or whatever, there is suddenly a new opportunity to sell them something to get rid of that hair! Is the demand being ‘sold to’? Of course – but at the same time, reinforced and promulgated through mass media.

See:

http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/119567296/abstract?CRETRY=1&SRETRY=0

(“Caucasian Female Body Hair and American Culture”, C. Hope, 1987)

In Europe for the longest time this was the case as well. Hence why so many “upper class” people wore white makeup etc. It showed that you didn’t need to be in the field like the farmers, and hence there was little washing too because only dirty people wash, while nobility was above this. Bring on the powder and have the serf remove the maggots from the wig please.

I am not surprised though that people perceive this as “white colonialism”, we’re still having a huge complex about things that we, in the west, have done in the past and it affects us to such a degree that we automatically conclude that whatever the other person is doing is because of us. It would be funny if it wouldn’t be so sad.

I, too, tried every high school summer, trying to read and tan, to no avail. Reading always won out. I now teach high school in the mid-Atlantic USA, and walk the halls daily among hundreds of white girls who spend all their leisure time at tanning salons. So the need to “lay out” to get tan has been replaced by the $$$ and time spent to become orange–because most of these girls do not really have a solid self image yet, so the tanner the better. At the same time, I see Chinese and Korean girls whose eyes are suspiciously shaped, and it breaks my heart. The African girls often wear wigs or straighten their hair, just like many of the African American girls. So far, the Indian girls straighten their hair, but nothing else. I admit that I see a small segment of the population, and teens are notorious followers. But I am not sure demand is being created, either in Asia or here. Global culture does not support healthy self-image at any age. Your post indicates the history behind the desire to look like someone else. Mass media may just multiply the images and therefore, demand.

This piece made me think of this ad that screened in Australia over summer.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1SCKUk3SxBI

In Australia it was read extremely differently to how Americans read it when the commercial made it onto youtube and caused a storm. To many Aussies, it was not about black and white, but about the social awkwardness of being stuck in the ‘wrong team’ section at a sporting match. We don’t have the same history with Africa as the US does, so I can see why it was read as extremely racist, and in many ways, the US commentary illuminated the way in which racism in Australia often remains quite invisible. But some then again some things seen in this ad by US audiences were just not really there in the aussie context…

the article starts well enough and I agree with the author that the situation is very complicated and that every situation is different ranging from class to race driven desire for skin lightening. However, this author really should look into the Indian/SE Asian communities much closer. It is pretty obvious that much of the “caste” system is driven by skin tone in Indian society and this has existed before colonialism and it’s discourse. Unfortunately the skin lightening APP really high lights the “caste” system in India, where if one marries out of one’s caste one may find herself killed for honor. So the above article still reflects american attitude of little understanding of other cultures and people.

A couple of comments; I suspect none of these will be a surprise.

India is at the intersection of many cultural narratives, and a number of these can be over-simplified to hair color. There’s North versus South, Hindu versus Islam, rural versus urban, no doubt caste, and so on. These narratives are no doubt crossed with narratives inherited from the colonial period, missionaries, etc. What other values might light skin represent in Indian pop culture, particularly Bollywood? Reducing these values to one axis, skin color, is a breathtaking trivialization, but that’s what a free market economy does–whether in the US, India, Japan, or elsewhere. Interesting, too, that this is an online product for virtual whitening. Is it used by both sexes? What are users trying to accomplish? Find a job, find a mate, get into the upper classes? Does Vaseline sell physical skin whiteners in India? Is there even a market for them, or is this purely virtual?

There is obviously an ironic sort of colonialism in Americans insisting on reading Indian skin color in terms of our own narratives, which are almost entirely irrelevant. But what’s really going on escapes me. I don’t think Vaseline is creating the demand; I expect it’s already there. The one thing I’m confident of is that skin lightening reduces all of these cultural issues to s single dimension.

It would be worth looking at other products (like hair straighteners) that may serve a similar function. Do these compress the same set of cultural issues into one dimension, or others?

I suspect that lighter-skinned Indian ethnic groups have some privilege relative to darker-skinned Indian ethnic groups. What the ad suggests to me, then, that light skin is aspirational for Indians in a way that’s classist, colorist, and ethnocentric — which, in practical terms, can be racist.

I don’t know much about pre-colonial India or about the ways in which class, caste, color, and ethnicity intersect. I think, however, that Americans reflexively read it as an imposition of Western standards rather than considering that it could be India’s own thing.

I think it’s still fair game to criticize Vaseline for the advertisement, though. Colorism and racism doesn’t become more right because it happened in India.

FWIW, skin lighteners are still available in the U.S., but the marketing has shifted to focus on “evening out” skin color and fading acne scars. You can still buy Porcelana and Ambi, for example, in many black neighborhoods.

“projecting American civil rights narratives onto other populations is not going to be the solution”

Someone once vaguely mumbled something about wrestling with the beam in your own eye before jumping on your brother’s back and forcibly removing the mote in his. Lurking globally, but snarking locally, seems to work well for me.

I have some issues with your framing the issue currently on the table as an “American” one, with the underlying assumption that it is a white American issue, and the subsequent assumption that people can’t possibly understand because there isn’t a framework for it, therefore risks being condescending and paternalistic.

Because much of the forefront against skin whitening (in all its forms) are of Asian ethnicity, including South Asian ethnicity. (I really wish I could link the Feministing post about this, but it is down) They have the cultural context; they have the necessary ties for understanding the phenomenon. But they are American (some of them), therefore they are as clueless as you before your trip to Shibuya? I don’t get it. Since when is there only one “American” perspective?

Sure, some of the ordinary commenters are relatively uneducated and reactionary, and an important step of any movement is spreading full awareness of the issues, including the historical background of the situation. But what makes you think that this isn’t happening? I’m getting a lot of “seems like” and “can’t help but wonder” and not enough solid facts. (and incidentally, the factory worker narrative does not cover all the issues of skin lightening. Japan, for instance, has been industrialized for a very long time)

Obviously it’s not “all about” colonialism. Rather, colonialism is an important part of race relations in Asia, and Vaseline is choosing to feed into the problem for cash.

See? No need to cast Vaseline as a moustache-twirling villain and India as a mass of oppressed victims, to know that there is a problem here.

You haven’t done the Asia advertising focus groups so you wouldn’t know why skin whitening is so much more pernicious than skin tanning products.

In these groups. People will choose who they go to lunch with based on their skin colour. The whiter the skin colour the more likely they are to be promoted. Skin whitening is hierarchical.

Sure a tan might speak of affluence and health but nobody got a job because they were tanned in the west. In Asia it goes without saying.

Skin whitening is wrong and the multinationals know it.

@ shing

In the more racially-homogenous parts of Asia (China, Japan, Korea) it might be mostly rooted in class-based discrimination rather than racism (though as Danah noted, it spills over to treating different foreign races differently). However, for someone who hails from South-East Asia, where countries tend to have large ethnic-Chinese diaspora, the boundaries between the two are blurrier. It does not help that the Chinese population is on the whole wealthier than the indigenous population, and are sometimes the subject of pogroms and riots (in Indonesia and Malaysia) or frequent targets of kidnapping (the Philippines).

@ danah

Whitening and fake tanning lotions might be rare in the States, but try taking a trip to Britain — when visiting a friend who was interning at MSR Cambridge a few years ago, I noted to my surprise that in the few years since my previous visit, fake tans (of the sort that makes the skin orange) have been so popularized by footballers’ WAGs (wives and girlfriends) that pretty much every other young working-class white women sports one. Good thing that the US, while statistically actually more unequal than Britain, at least does not have this kind of class-based boundaries (or, at least, not yet).

Charles is right. In India for example, matrimonial ads in newspapers (which very much still exist and are still used by a huge number of parents to find partners for their parents) openly state that families/bridegrooms want ‘tall, fair, beautiful’ brides. ‘Fair’ is synonymous with beauty, dusky/dark-skinned is not. It affects people psychologically, even financially – poor people who have a fair daughter can get more dowry, for example. All awful practises, but they do exist nevertheless. Skin whitening is wrong, and encouraging it is wrong. Vaseline made a big mistake. All my Indian friends who are on Facebook hate the Vaseline app as much as I do. Omnicom deserve to be whacked – and the client even more. Educated people are probably laughing at them – and they’re the ones on Facebook. Their target audience, who’ll actually buy the crean, probably don’t even know what Facebook means.

Interesting too that many teens today (at least in Europe) want to be pale. I certainly think Europeans and Australians are less tanned than twenty years ago. There’s classism in this too: we know about skin cancer. You’re stupid if you’re tanned. Although teens I’ve talked to about this always mention Kirsten Stewart and Twilight.

So a cultural infatuation with vampires coincides with knowing that the sun is dangerous…

Here’s my attempt at answering the question at the end of the post: Online publications (whether it’s a zine or blog) are already starting to provide the local context that we need to understand these issues. Global Voices Online is a great example of a bridging and contextualizing engine. Of course, much of the information is not so neatly piled together and is strewn all over. So I guess it’s a matter of getting to it, spreading the word and connecting it to the cries of “OMG WHITENESS CREAM.”

But I do have a question about one of the assumptions: How is the USA challenging colonialist oppression in the first place? (I’m not saying they aren’t, because they certainly do a lot of human rights advocacy as well as freedom of press advocacy. The thought came to mind because for mundane matters like young women picking up skincream, or perhaps for the commercial space, I don’t really see the US having a role to play (other than the promotion of free & fair (?) trade).) It’s an open question for thought anyways.

Thanks for the post.

via BoingBoing

Really enjoyed reading this.

Makes me think Star Trek’s ‘Prime Directive’ really means isolationism. 🙂

If we are usually wrong, usually get skewed impressions when we gaze off the shores our little islands, the solution isn’t, not to look, it is to be careful judging.

Interesting that the production and marketing of the fabrication of identity perpetrates and is a product of – class.

I only found out about skin whitening 3 months ago when a friend got to Pakistan, where her relatives got there hands on what little tan she managed to get during finals week. This Vaseline capaign was the first time I got a glimpse at how prevalent the “white is beautiful” ideology really is in some places around the world.

Good for the advocacy groups for bringing attention to this matter. But, I think little can be achieved until the societies themselves (e.g. Indian, Japanese) start having dialogues among and between themselves to understand why exactly they believe that “white is beautiful.” This is the classic you-have-to-want-to-help-yourself thing. If human rights groups get too gung-ho, which happens, this situation could easily turn into a “white man’s burden” scenario. *shudder*

Last note: Frankly, reading in the hot sun sucks. I’m more of a hammock-in-the-shade outdoor reader.

@michel I’m Malaysian by nationality and ethnically Chinese. I also lived in the Philippines for 6 years(and my neighbour was kidnapped! it was weird. it turned out okay.).

I think we agree – I was saying that asian racism is rooted in far more than skin colour and doesn’t break down neatly into skin colour categories. In Malaysia for example, the Malays have much of the “power” thanks to retarded “bumiputra” laws(pretty much – the country was made for the Malays. go institutional racism!) and they certainly tend to be darker skinned than the Chinese. Meanwhile, the Eurasians(descendants of the colonists) who have lighter skin are still slightly resented. In Indonesia, I think they were actually actively persecuted since they were identified as being “dutch” and not “indonesian”.

Finally, someone with a sensible perspective on this issue. Thanks Danah.

I grew up in India – at a very early age, like any other kid from a middle-class family, I learned how to navigate through the complexities of caste, religion and class. I witnessed different social complexities of race and nationality when I moved to US. There is some role that each of these play in this issue – but what most people ignore is economics. The reason these products are popular is simple – people buy them and buy them a LOT. The idea that “fair is beautiful” is very deeply ingrained in the Indian psyche – and this has been attributed to many things, including colonization, caste system and the north-south divide – but the truth is, it exists and without much complain. So, naturally – the product manufacturers thought – if people didn’t find the product objectionable – why would they object to an app that does the same?

The Western uproar is interesting – and is rooted in some amount ignorance. The issue is about the perception of beauty and not of race. Obviously, many commenting on this topic have no idea what the idea of beauty is in India – and hence this looks like an obviously “racist” app. There are people in India who think this app (and the product) is despicable – but for different reasons. I can pull out a lot of western counterparts to the same issue – like tanning salons, the obsession with staying skinny etc – but none of them comes close to explaining the complexity of this issue. It surprises me, how as part of the a “flat world” – we still don’t take off our lenses of comfort when looking at the socio-cultural events from other parts of the globe. In some countries in Africa – big is beautiful. What do you think they think of bulimic teenagers from the west?

This is why I love EthanZ’s work – if the internet is going to bring us together as a planet – we need to be ready to face things that we are not comfortable with – and questioning ourselves whether that discomfort is due to our lack of knowledge and context. And more importantly, the desire to explore and try to understand the context with non-judgmental eyes. This means, before you share “Look at this racist ad from India” – you pause and ask yourself is it racist in India or racist in the USA – or simply, ask an Indian friend!

I’m love to understand why white people from the American North(east) love to tell other people they’re being racist. Also, WTF is up with the “Global South” nonsense? I grew up in the South and never heard that phrase. I suspect that those using it did not.

I’m all for changing the world, but I’d like to suggest that bitching about places you’ve never been to and don’t understand isn’t the right way to do it.

Being less insightful than the rest of your commentators and you, I’ll just say I thought of the tanning vs. whiting thing yesterday as well when I saw the outraged yelling about whiting and saw tweets about which tanning products to use before attending a conference where dresses would be worn.

Being an Indian studying in the undergrad, the only emotion I can muster is a hearty laugh. Back home skin whitening creams are on the same plane as lipstick, nailpolish and hair spray. Yes, it’s superficial, hollow and vain, but it’s not racist. As has been said before — it’s a beauty and social stature thing, not a race thing. If tanning salons aren’t decried as racist, I see no reason why whitening creams should be either.

I won’t speak to the South East Asian issue, since it is the most-discussed above, but I’ll make two other observations. First is that the European desire to remain white is very very old indeed, going back to the Ancient Greeks. It is only in the mid-20th century, when travel supplanted indolence as a sign of the leisured classes, that the tanning salon became plausible.

And then I would like to point you, Danah, to a magnificent article by the late Joe Wood, “The Yellow Negro,” on the infatuation with blackface amongst Japanese teenagers in the early 90’s. It originally appeared in one of the great semi-academic journal issue of all time, TRANSITION’s special issue on Whiteness, table of contents here: http://www.transitionmagazine.com/backissues/73.htm

Mr. Gunn — The Global South doesn’t refer to the American South (assuming that’s what you meant by “the South”), but rather, the fact that most wealthy, industrial nations are located in the Northern Hemisphere, while the majority of poorer, postcolonial nations are in the Southern Hemisphere. Global North and Global South are terms many academics use to describe worldwide social and economic divides, without using terms like “first world” and “third world” or “developed” and “developing,” which imply a forward arrow of progress (for more, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/North-South_divide).

I don’t think you’re right that this is primarily an American outrage; I’ve seen numerous tweets from Arab communities on Twitter, and in the Arab blogosphere(s). Arab communities are also heavily targeted by whitening products (when I lived in Morocco, the product du jour was “Fair & Lovely,” and its advertisement showed a woman not getting a job on TV, then lightening her skin, then going back and getting that very same job).

Of course, Arabs are not Indians, and you’re right to question whether Indians are upset by this…at the same time, as this is a virtual app and not a locationally-targeted product, it affects all of us, including darker-skinned Americans, many of whom have expressed anger or annoyance at the app.

Skin-whitening adverts ignite race row in India

I would suggest you check South Asian news sources in English.

“And why aren’t Americans critical of the tanning products that Vaseline and related companies make? Frankly, I’m struggling to make sense of the complex narratives that are playing out right now.”

They really aren’t that complex. Sun tans are temporary.

Your response is so simplistic it almost seems like your looking for an out.

The Times of India

I’m asian and vietnamese to be exact. about a decade ago, my mom, who is a petite woman and looks pretty good, went to our family doctor and asked for some medication to be fatter. the doctor laughed at her and told her to go home. if you want to know, she also hates being tan. i laugh at this, because i think that being tan is pretty. But from my experience, i think the reason that this happens is because “being fat and white” means you are not working in the fields and have servants who take care of you, which makes you appear upper class. my two cents.

Highly relevant and timely…Global Voices India post: http://globalvoicesonline.org/2010/07/23/india-fair-lovely-and-facebooked/?utm_source=twitterfeed&utm_medium=facebook

Very interesting thoughts- I do think it’s more complicated and related to the culture of the country. This is why my husband, in his new job of supporting international locations, studies up on cultural statutes before even talking with those people, so he doesn’t offend. Also, (danah- you will understand my ultimate “music geek” coming out) there is a great musical that deals with this exact issue, set in the Caribbean called “Once on this Island”

I think you pretty much nailed it. But calling Vaseline racists is unfound and these companies are just playing on the way people think in these regions. Apart from Vaseline there are way too many Indian brands doing the same thing. That said I think you should take a look at this comic that explains the scenario.

http://www.flyyoufools.com/indian-fairness-creams-comic

While I understand your logic in analogizing skin-whitening to tanning, I find it faulty. Yes, both phenomena deal with skin tone, but it’s naive to assume they necessarily have they have the same origins. Do white people undergo painful and risky surgery to flatten the bridges of their noses, create epicanthic folds, or acquire other phenotypically “non-white” features?

Madeline – I understand your point but beauty has driven all sorts of painful and risky modifications to appease cultural constructs, some of which are driven by race, some of which are driven by class, some of which are driven by age, etc. Smaller noses, implants from breasts to calves, vaginal tightening, freckle removal, hair straightening and curling, liposuction, etc. In many societies, people no longer understand the historical roots of what makes something in that society “beautiful” making it hard to untangle colonial histories with contemporary aesthetics and making locals really resistant to being told that they are being oppressed when they reinforce aesthetic values that have deeply problematic roots.

(Hell, try convincing women in the US to stop wearing high heels because of the sordid history of those damn shoes; we know that they’re physically dreadful but we’ve also seen feminist moves to reclaim high heels ignoring the past.)

I’m not justifying the historical roots of these markers but I still find it deeply problematic to see a bunch of Americans telling Indians that they’re living out racist values in their desire for whitening products. We’ve got a lot of work to do on our own turf. And I also think that by holding on to our own racial histories, we fail to understand the caste narratives that shape a lot of Indian society. And the ways in which things like whitening have more to do with caste than anything else.

So if anything, I think that we should be complicating the stories we’re hearing and opening up space to listen to people whose experiences and struggles with these issues differ from our own.

It’s not just about the product, it’s also about the context!!!

Even in africa, lot of people (especially women) use tanand others products to make their skin more white…

The most effective skin lightening cosmetios are those that contain mercury. Mercury specifically inhibits the enzyme that makes skin dark colored. Use of skin-lightening cosmetics containing mercury is one of the major causes of mercury poisoning in Africa.

LatinAmerica is the other region of the world where this is so true and prevalent.

There is a saying in Mexican culture when marrying a paler tone person that people are actually “improving” the “race”.

Also please note the actors in Sopa operas and movies.

The rarely reflect the realities of the population.

This could play dangerous dynamics in the US as the largest minoroty is becoming the majority soon.

Once we all become so multicultural then the game of shades is so confusing and threatening.

Your post is insightful.

On a last note creams like this one have been very very popular in the region.

Being the most famous one, “Concha Nacar” which is made out of sea shells.

I don’t know the chemical contents but it is probably abbrasive and not healthy.

As an American-Indian man (I use this term fleetingly, in order to give myself some sort of leverage in saying that I know what I’m talking about) I was raised around the idea of skin-bleaching and whitening products. From an ethical perspective: these archaic forms of beauty are truly disturbing. But just because it discusses a minority issue, that doesn’t mean its worse than ideals of beauty in the caucasian community. People tend to look at things on a hierarchical scale, outraged by the black-community’s need for hair extensions, or eyelid surgery for asian women, or in this case, skin-bleaching creams for indian men. These ideals, although outrageous, aren’t on a different scale than caucasians getting tanned, or wanting to be extremely skinny, or going bleach blond, or partaking in the silliness of silicon implants.

The truth is this: our colonial history has left us all with some absolutely atrocious ideals of beauty. But they exist, and they need to be dealt with in the appropriate manner.

Vaseline is, rather smartly actually, using social-media to activate an existing product, for an existing demographic that has an existing need. And that’s okay. We need to get out of our ethnocentric perspective to look at things from the demographics’ point of view: there is nothing wrong with marketing a skin-bleaching formulae to a market that utilizes it, on quite a regular basis actually. There is nothing unethical about what they are doing.

But the question is: how do we polish-off our archaic, colonial, systems of beauty? And can that be done through marketing.

Heyy Congrats!!!!…. One small victory over Unilever!!!! They have taken off the “Vaseline Men Be Prepared” app from facebook, finally!!! yayyy!!! now only if we could get them to stop their racist advertisments in Asia and Africa………… and stop marketing their con products that claim to whiten skin!!! Most of all, if people could stop thinking their skin color makes them different!!!!

Pls join the campaign: http://www.change.org/petitions/view/unilever_please_stop_marketing_racist_products

“So if anything, I think that we should be complicating the stories we’re hearing and opening up space to listen to people whose experiences and struggles with these issues differ from our own.”

I like that idea– always important to look at things in the more nuanced way.

I don’t know what to think, though. I have a Vietnamese friend who lives here in the States and she’s always using whitening cream. Or she’ll stay inside all summer to avoid the sun. She was on the track team with me once and once winter ended she brought a gigantic UV blocker to cover her face (it looked like a mask and she had to hold it up off her face), and she quit long before the end of the spring. She’s obsessed with beauty. A girl brought up that this beauty practice was rooted in classism, and the girl responded, “I know that, but that’s not the point– it’s just different where I live,” which I agreed with. On one hand, it strikes me as a bad thing and bothers me somewhat, but who are we to say anything? Is it better to say or not say anything? I don’t know. It’s very complicated :/